When HBO’s The Gilded Age first aired, the ornate mansions and whispered social rivalries drew viewers in — but the costumes? They stole the spotlight. The gowns, suits, gloves, and jewelry didn’t just clothe the characters; they narrated their social ambitions, hinted at their secrets, and revealed unspoken rivalries.

At the center of this opulent wardrobe is Kasia Walicka-Maimone, the series’ costume designer, whose vision is rooted in a single philosophy: history informed, not reproduced. For her, costume design isn’t about perfectly replicating the past; it’s about reimagining it through a modern cinematic lens — creating clothes that honor the 1880s while keeping today’s audiences enthralled.

Kasia Walicka-Maimone is a Polish-born, New York–based costume designer known for blending historical accuracy with cinematic style. She’s behind The Gilded Age’s lavish 1880s wardrobes and has worked on films like Bridge of Spies, Moneyball, Capote, and A Quiet Place. Her process involves extensive visual research, using color, texture, and silhouette to tell a character’s story.

The Gilded Age’s Costumes: From the Canvas to the Screen

To capture the essence of New York high society in 1882, Walicka-Maimone turned to fine art — most notably the portraiture of John Singer Sargent. Sargent’s work, celebrated for its sumptuous fabrics, luminous colors, and the intimate psychology of his sitters, offered a perfect roadmap for bringing the Gilded Age’s elite to life.

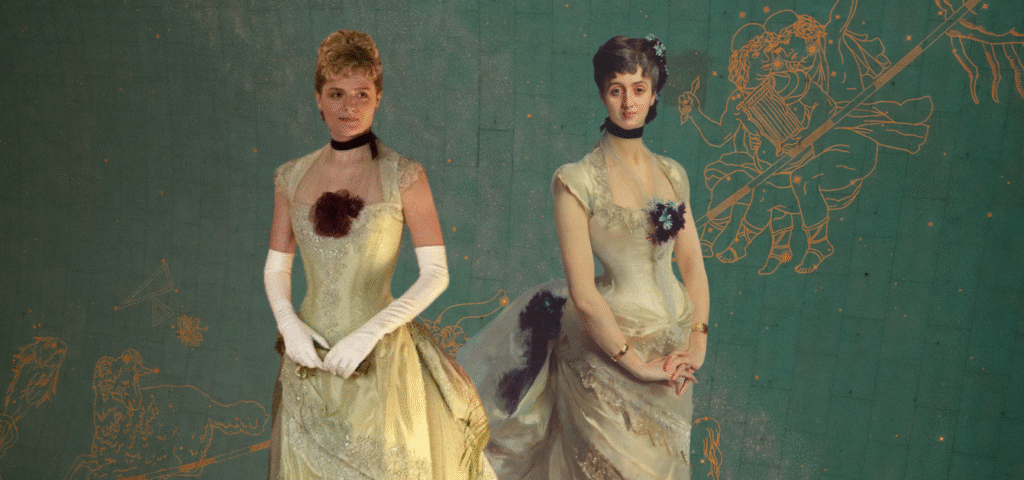

Two standout translations include:

- Bertha Russell’s burgundy and ivory lace gown — modeled after Sargent’s Mrs. Hugh Hammersley (1892). In both painting and costume, the deep color radiates confidence and luxury, while the lace detailing softens the assertiveness with grace.

- Marian Brook’s pale yellow silk dress, accented with a plum blossom corsage and a black velvet choker — inspired by Portrait of Madame Paul Poirson (1885). It’s a portrait of innocence, yet the choker hints at an emerging boldness.

But Sargent wasn’t the only influence. Walicka-Maimone and her team studied the works of James Tissot, whose paintings are practically fashion catalogues of the era, and Giovanni Boldini, famed for capturing motion and sensuality in clothing.

An Archive of Forty Thousand Images

Research was exhaustive. The costume department curated a digital archive of over 40,000 images — portraits, fashion plates, museum garments, and candid period photographs. This enormous visual library wasn’t just about clothing; it captured the posture, gestures, and social codes embedded in the way people dressed.

For example:

- Hat placement could signal social confidence or submissiveness.

- Glove length indicated formality, wealth, and even marital status.

- Color choices reflected the unwritten rules of class — old money favored restraint, while new money embraced boldness to assert presence.

Pandemic-Era Museum Access

One unexpected advantage of designing during the pandemic was unprecedented digital access to museum collections. With leading institutions — from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute to the Victoria & Albert Museum — putting high-resolution images of garments online, Walicka-Maimone could study embroidery techniques, lace construction, and even the wear patterns on original pieces.

This access allowed the team to replicate the craftsmanship of the 1880s:

- Hand-finished seams.

- Period-accurate fastenings like hook-and-eye closures instead of zippers.

- Embroideries based on authentic 19th-century patterns.

Costumes as Social Chess Moves

In The Gilded Age, clothes aren’t just beautiful — they’re strategic. Every gown, hat, and glove is a calculated move in the high-stakes game of New York’s social ladder. Walicka-Maimone uses costume as a visual language, revealing who holds power, who’s grasping for it, and who’s teetering on the edge of losing it.

Old Money: Power in Restraint (e.g., Agnes Van Rhijn)

The established elite operate under an unspoken rule: true wealth doesn’t have to shout. Their wardrobes are an exercise in understatement — a subtle reminder that they’ve been here for generations and have no need to dazzle for acceptance.

- Fabrics: Dense, weighty materials like heavy silks, velvets, and brocades, which drape with quiet authority.

- Palette: Deep jewel tones, navy, black, and muted golds — colors that convey gravitas, not trendiness.

- Style: Minimal embellishment, controlled tailoring, and classic cuts that change little over the years, underscoring their timelessness.

- Agnes Van Rhijn: By resisting flashiness, Old Money women reinforce their position: they are the standard, and others must aspire to them.

New Money: Fashion as a Declaration of War (e.g., Bertha Russell)

For ambitious newcomers, fashion is an entry ticket to the upper crust — and a weapon to outshine rivals. Bertha’s wardrobe isn’t just lavish; it’s designed to be impossible to ignore. She uses clothing the way a general uses troops: to advance, intimidate, and claim territory.

- Fabrics: Lighter, fluid silks, shimmering satins, and metallic brocades sourced from Europe’s most fashionable ateliers.

- Palette: A gemstone spectrum of scarlet, emerald, turquoise, and lavender — hues that demand attention in a sea of navy and black.

- Style: Paris-inspired couture with daring silhouettes, sculptural bustles, and towering feathered hats.

- Accessories: Diamonds, pearls, and gold filigree pieces worn in abundance — a visible declaration of wealth and ambition.

- Symbolism: Every outfit is a public announcement: I belong here — and I may just take your place.

The Invisible Players: Servants’ Wardrobes

Even the servants’ clothing serves a purpose in the visual hierarchy. Their uniforms are intentionally muted — blacks, browns, and grays — providing a neutral background that makes the society women’s dresses appear even more vibrant and imposing.

- Function: The lack of color and adornment visually “erases” servants from the foreground of scenes, mirroring their limited social agency.

- Symbolism: Their quiet, uniform appearance reinforces the class divide, ensuring that all eyes — and all influence — remain with the women they serve.

In this way, The Gilded Age turns fashion into a form of psychological warfare. The wrong dress can signal desperation. The right one can seal an alliance, crush a rival, or cement a legacy. Clothing isn’t just part of the set design — it’s part of the plot.

The Gilded Age The Men’s Wardrobe: Quiet Power Dressing

While the women’s costumes dominate conversation, the men’s wardrobes are equally intentional.

- Frock coats and morning coats for daytime respectability.

- Tuxedos and white tie ensembles for evening galas.

- Accessories like top hats, pocket watches, gloves, and walking sticks reinforcing wealth and propriety.

- Color play is subtle — navy, charcoal, and black dominate, with patterned waistcoats providing a flash of personality.

In The Gilded Age, Black men like Arthur Scott wear mostly gray suits for both historical and symbolic reasons.

In the 1880s, muted tones like gray and charcoal were common for professionals, projecting respectability and avoiding social risk in white-dominated spaces. For Black professionals, this conservative style was part of “respectability politics,” using polished, understated dress to counter prejudice. Costume designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone uses the gray palette to highlight dignity, discipline, and the careful navigation of racial and social boundaries.

Fashion as Narrative

Fashion in The Gilded Age isn’t just there to look beautiful — it works like another layer of dialogue, quietly telling the viewer what’s happening beneath the surface. For costume designer Kasia Walicka-Maimone, every fabric choice, color palette, and seam is deliberate, designed to track a character’s personal journey. When someone gains confidence or begins to claim their place in society, their wardrobe subtly evolves — muted tones give way to richer, more saturated colors, and fabrics become more luxurious. Conversely, a social setback might appear not in words but in a slightly outdated gown, a less elaborate hat, or jewelry that feels modest compared to earlier scenes, signaling that their position has shifted. These changes are rarely announced; instead, they unfold visually, allowing the audience to read the clothes like clues. In this way, The Gilded Age turns fashion into a form of subtext — a parallel storyline that runs quietly alongside the spoken drama, enriching the narrative without ever needing to say a word.

A Moving Museum

What Walicka-Maimone has created is more than television costume design. It’s a traveling art exhibition, a collaboration between the past and present. The series treats each episode like a curated gallery of living portraits, with gowns and suits that wouldn’t be out of place in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

It’s why viewers can’t help but pause, rewind, and screenshot — The Gilded Age isn’t just a show you watch; it’s one you study.